Switching to CCR Diving

Switching to CCR Diving – An Overview

3rd October 2025

Motivation matters

The limits of open circuit diving

There usually comes a point in a tech diver’s life when it’s time to learn again. That something could be sidemount, cave, DPV, or trimix. Aware of the cost of helium, many divers undertake the normoxic trimix course because trimix sounds cool, and they want to learn new things and challenge themselves. Once divers complete the course, most know that they will do little to no trimix diving again on Open Circuit (OC).

This is likely the reason you are reading this. Switching to CCR diving often feels like the next natural step. The technology offers a way to go deeper, stay longer, and make helium use much more affordable. This doesn’t mean OC is then forgotten. I still enjoy diving single cylinders, twinsets, sidemount, and CCR equally. Each configuration has its own strengths, benefits, weaknesses, and limitations. Rather than replacing OC, CCR gives you options, and who doesn’t like options?

What attracts divers to CCR?

Of course, there are numerous other reasons for switching to CCR. Usually linked to what type of diving a person wants to do. One of the strongest drivers has already been mentioned- cost. Helium savings are dramatic and open the door to more frequent deep diving. If cost is no longer a barrier, helium can be increased to reduce narcosis. Another motivation is decompression efficiency. A CCR maintains a constant setpoint of oxygen, so decompression is more optimised than on OC. Divers can complete the same profile with reduced deco obligations. Conversely, they can accept a conservative approach and reduce decompression stress.

For many, switching to CCR ties into a desire for exploration. CCR for wreck and cave diving offers longer bottom times at depth, with more efficient decompression. Even at recreational depths, a rebreather allows longer dives without the need to carry large volumes of gas.

Wildlife encounters

For me, one of the most noticeable changes when I learned to dive a rebreather was how marine life responded to my presence. On OC, exhaust bubbles are loud and intrusive. Fish scatter, turtles swim away, and large animals keep their distance. On CCR, everything changes. I have had turtles come bounding straight towards me, literally out of the blue, pressing nose-to-nose. Manta rays have done somersaults around me within arm’s reach, holding eye contact as they likely wonder what I am. For divers motivated by nature, switching to CCR is a game-changer.

Learning new things and challenging yourself

CCR diving appeals to divers who enjoy mastering new skills. Some people thrive on complexity, equipment setup, and dive planning. Rebreathers offer all of this in abundance. For others, the motivation is personal challenge: the satisfaction of learning something demanding and becoming competent at it. There is also a subset of divers who simply like technical equipment. They enjoy understanding how systems work, experimenting with different configurations, and refining their setup. CCR provides endless opportunities to do this, and it can be part of the appeal.

When motivation doesn’t match reality

Not every motivation stands up in practice. Photographers and videographers often train on CCR because they expect closer animal encounters. While this reasoning is valid, many professional videographers I have spoken to no longer use their rebreathers. The reason is logistical. Travelling with large amounts of camera equipment is already challenging. Adding a rebreather, sofnolime, cylinders, spares, and tools makes it worse (they’re often in remote locations). For many, it becomes a hindrance rather than a tool.

Photographers face an even harder problem. Staying current on a CCR requires frequent diving and regular refreshing of skills. Combining this with casual photography is challenging, especially when dives are infrequent. In practice, many photographers cannot afford to devote time to switching to CCR diving; photography is their priority, and something has to give.

CCR diving takes commitment

CCR is challenging. It is complex and not always intuitive. Decompression obligations may increase compared with OC. CCR may also increase exposure to hazards such as hypoxia, hyperoxia, and hypercapnia. It requires discipline and adds significant task loading. A rebreather cannot think for the diver. Electronics, sensors, and alarms provide support, but they do not replace human judgment. The greatest risks come not from the equipment itself, but from human error.

Balancing rewards with responsibility

CCR diving offers extraordinary rewards: longer dives, reduced helium costs, optimised decompression, closer wildlife encounters, and greater comfort underwater. It also provides intellectual challenge and the satisfaction of mastering complex equipment. But these rewards are balanced by increased responsibility. CCR diving demands time, money, and discipline. It is not suitable for every diver, nor should it be seen as the inevitable next step for everyone. The decision to switch to CCR should be based on honest reflection: what kind of diving you want to do, and whether you are ready to commit to the discipline that CCR requires.

Prerequisites and Training Pathways

Previous diving experience

Although it is possible to learn to dive on a rebreather with no prior technical diver training, previous OC technical training makes the transition smoother and safer. Divers who already hold decompression or trimix certifications have a foundation of essential skills. Without them, switching to CCR can feel overwhelming. If a diver is simultaneously struggling with basics such as trim or ascent control, training can become unnecessarily difficult. For this reason, a strong grounding in technical diving is one of the most valuable prerequisites for CCR.

Practical CCR prerequisites

I have mentioned that divers should have good fundamentals before progressing to CCR diving, but what are they?

- Maintaining stable trim and buoyancy in a drysuit or wetsuit is essential for deco and penetrations.

- Conducting accurate and controlled ascents.

- Being able to follow a dive plan.

- Effective use of propulsion techniques such as back-finning and helicopter turns.

- Applying basic decompression theory and gas management principles.

- Demonstrating good awareness, communication, and positioning.

Training agencies do not list these skills as formal prerequisites, yet they strongly affect how smoothly a course runs. They also ultimately determine whether you pass or fail. A student learns all of the above on OC technical diving courses, which means they have a strong foundation before switching to CCR.

What a CCR can and can’t do

One of the strongest motivations for switching to CCR diving is the dramatic reduction in gas use. An OC 60-metre dive with trimix in a twinset might require 2,500 litres of helium. On CCR, the same dive may need only 310 litres in a 3-litre diluent cylinder. This difference makes regular deep diving financially realistic. It also allows divers to use mixes with higher helium content than they would on OC, reducing narcosis further without making costs astronomical.

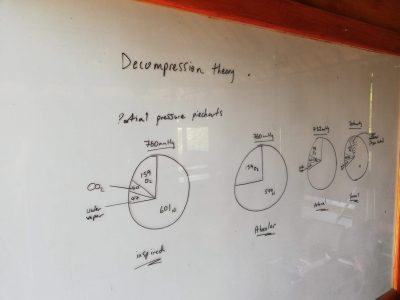

Divers sometimes describe a CCR as a “best-mix nitrox machine.” This is a simplification, but it illustrates the point. By maintaining a setpoint, the rebreather delivers a stable partial pressure of oxygen (PPO₂). This results in a higher oxygen fraction at most depths compared with OC, and therefore a lower partial pressure of nitrogen (PPN₂). This is especially important as a diver ascends- PPO₂ drops on ascent on OC. On CCR, it doesn’t. Reduced nitrogen uptake reduces decompression stress, which is a further incentive for switching to CCR.

Extending dive opportunities

CCR diving makes demanding dives possible. Wreck divers benefit from longer bottom times without carrying multiple stages. Cave divers can go deeper with reduced logistical complexity. An invaluable component of diving in overhead environments is having more time to deal with a problem in the absolute worst-case scenario, such as a siltout. Not an option on OC. Even recreational divers notice advantages: Notably greater NDLs on a 30m dive (100ft), for example.

For technical divers, the rebreather becomes an enabling tool. Instead of limiting dives to what is practical on OC, CCR extends the feasible range of profiles, allowing more ambitious exploration with optimised decompression. This is one of the strongest arguments in favour of switching to CCR.

What CCRs can’t do

There are limits to rebreathers. Despite the benefits, a CCR does not simplify diving. Decompression obligations remain, and in many cases, they become more complex. Dive planning is still essential. A CCR also cannot remove risk. Instead, it can increase the risk of certain hazards, including the three H’s- hypoxia, hyperoxia, and hypercapnia.

Electronics and alarms provide support, but they do not replace the diver’s brain. A CCR cannot think for you or tell you what to do when a fault occurs, and can’t prevent human error. The blob of jelly inside your skull remains the most important piece of equipment you carry.

Finally, a rebreather does not eliminate the need for open-circuit gas. Every CCR diver must carry adequate bailout, sized to cover the worst-case scenario. The rebreather changes how much gas you use when things go well, but not the need for redundancy.

Human factors and misconceptions

One of the biggest risks in CCR diving comes from human behaviour. Drift, complacency, and normalisation of deviance are real dangers. Skipping checklists, rushing pre-dive checks, or neglecting maintenance are the causes of many accidents. A diver who assumes the CCR “does everything” is misunderstanding the technology and underestimating the risks. More on these later.

Balancing benefits and responsibilities

The rewards of CCR are clear: longer dives, helium savings, optimised decompression, closer wildlife encounters, and greater comfort. But these rewards are balanced by responsibility. A rebreather expands what is possible, yet demands a higher level of vigilance, consistency, and commitment. For divers switching to CCR, recognising this balance is crucial to long-term safety.

The Costs of CCR Diving

How much!?

Switching to CCR diving usually invokes a panic attack about the cost. To make matters worse, a rebreather is not just an upfront investment; it requires ongoing spending on consumables, training, service, and spares. Some divers are drawn to CCR because of the potential helium savings compared with OC. While this is true, divers need to weigh the savings against the total cost of ownership.

Upfront investment- the unit itself

A new rebreather typically costs between $7,000 and $10,000 (around £5,500–£8,000 or €6,500–€9,000) depending on the make, model, and options chosen. Popular units at the technical level sit at the higher end of this range. Recreational rebreathers may be cheaper, but they may not suit divers who later want to do serious decompression diving.

Many divers also purchase accessories: spares, travel cases, custom harnesses, or electronics upgrades (e.g. the Nerd 2). These extras can easily add another $1,000–$2,000 to the bill (£800–£1,600 or €900–€1,800).

Training costs

CCR training costs more than typical OC courses due to the duration, equipment needs, and lower instructor-to-student ratios. Initial entry-level training usually costs between $1,500 and $2,000 (£1,200–£1,600 or €1,400–€1,800). Advanced CCR training, such as normoxic or hypoxic trimix, adds similar amounts per course. Cave CCR adds another expense if divers pursue overhead training.

For divers switching to CCR, training is not just an expense but a recurring investment. Someone progressing from air diluent to normoxic and hypoxic trimix can spend $4,000–$6,000 (£3,200–£4,800 or €3,600–€5,400) on training fees alone. The devil’s advocate here is that you aren’t paying for them all at once; they are staggered as you incrementally learn. Moreover, what else are you going to spend your money on? We all have passions- don’t feel bad about spending money on yours!

Gas costs: OC versus CCR

Helium is where CCR delivers the largest savings. On a 60 m trimix dive (18/45), an open-circuit twinset typically requires around 2,160 L of helium. A CCR diluent cylinder (3 L at 200 bar, 18/45), contains 270 L of helium. This order-of-magnitude reduction is why regular trimix divers often find CCR more economical over time.

Oxygen is cheaper than helium, yet still matters. A 3 L O₂ fill commonly costs $10–$20 (£8–£15 or €9–€18), with local variation and occasional standing fill fees.

Sofnolime

Sofnolime removes CO₂ from the loop. It must be replaced after a certain number of hours dived (set by the manufacturer). Typical 20 kg tub prices:

-

US: about $219 (Dive Gear Express)

-

UK: about £97 Submarine Manufacturing & Products Ltd

-

Europe: about €179 Deepstop

Assumptions: Using 2.5 kg every 4 hours. Total cost calculated for 50 and 80 hours of diving:

-

USA: $333 (50 h). $533 (80 h)

-

UK: £152 (50 h). £243 (80 h)

-

Europe: €280 (50 h). €448 (80 h)

Oxygen costs (2-hour refills)

Assumptions: 3 L cylinder at 200 bar (600 L capacity). Benchmarks: US $0.013/L (≈ $0.40/cu ft), UK £0.037/L, Europe €0.06/L.

With 2-hour refills: 50 h → 25 fills; 80 h → 40 fills.

-

USA: $195 (50 h). $312 (80 h)

-

UK: £555 (50 h). £888 (80 h)

-

Europe: €900 (50 h). €1,440 (80 h)

Trimix diluent costs (2-hour refills)

Assumptions: trimix 18/45 in a 3 L cylinder at 200 bar (600 L total; 45% He → 270 L He per fill). Benchmarks: US $0.088/L, UK £0.075/L, Europe €0.085/L → ≈ $24 / £20 / €23 per fill.

With 2-hour refills: 50 h → 25 fills; 80 h → 40 fills.

-

USA: $600 (50 h) / $960 (80 h)

-

UK: £500 (50 h) / £800 (80 h)

-

Europe: €575 (50 h) / €920 (80 h)

Servicing and spares (annual average)

-

USA: $1,100

-

UK: £730

-

Europe: €805

Includes oxygen sensors (three per year), batteries/O-rings/hoses/service kits, and manufacturer servicing averaged across the cycle.

Annual totals

Air or Nitrox CCR

Totals = Sofnolime + Oxygen + Servicing; excludes training and travel.

-

USA: $1,628 (50 h) / $1,945 (80 h)

-

UK: £1,437 (50 h) / £1,861 (80 h)

-

Europe: €1,985 (50 h) / €2,693 (80 h)

Trimix CCR

Totals = Air/Nitrox totals + Trimix diluent costs (2-hour fills).

-

USA: $2,228 (50 h) / $2,905 (80 h)

-

UK: £1,937 (50 h) / £2,661 (80 h)

-

Europe: €2,560 (50 h) / €3,613 (80 h)

Balancing cost and benefit

CCR diving can save money for divers who often dive deeper. The per-dive helium savings are dramatic. However, the unit itself, consumables, training, and service keep overall costs high. For occasional divers who only make a handful of trimix dives a year, the financial case is weaker. For regular technical divers, the economics make more sense, provided they also commit to the discipline required. This is all compared with doing the same dives on OC.

When switching to CCR diving, divers should view cost not only as money spent, but as part of an investment in long-term safety and competence.

Which rebreather should you buy?

That is not an easy question to answer. Many rebreather brands exist, and most are well-built and reliable. Have you ever heard the expression, “every boat is a compromise”? The same applies to rebreathers.

Take the JJ-CCR, as that is what I have owned for the last nine years. It is simple and easy to set up, reliable, robust, easy to buy spares for and get serviced, and capable of all kinds of diving- deep, cave, wreck. It is also heavy and bulky, which makes travelling with it less enjoyable. Additionally, it is primarily designed for use in a drysuit, so seahorse trim is the default setting in a wetsuit (carbon fibre tanks solve this problem).

Ask around

Discussion of which rebreather to buy requires a dedicated, separate article. Divers need to research to make an informed choice for their own needs. Talk to lots of divers who own different brands. Talk to instructors who teach on multiple brands. Each will have a preference, but remember, it is their preference for their needs.

It always comes back to what kind of diving you want to do. Drysuit or wetsuit, or both? Do you intend to travel a lot? Will you be undertaking wreck or cave penetrations- would a sidemount rebreather be better if so? Moreover, should you get an ECCR or MCCR, that’s akin to manual or automatic cars. Each has advantages and disadvantages.

The CCR Learning Curve

Why the CCR learning curve feels different

The transition from OC to CCR is not straightforward. Skills that felt instinctive on OC suddenly feel alien on a rebreather. For divers switching to CCR, this gap between old reflexes and new demands often comes as a surprise.

Unlike with OC, breathing in and out does not directly affect buoyancy. Instead, divers control buoyancy by managing loop volume, adjusting the BC, and using the drysuit. This three-way balance is unfamiliar and overwhelming. Loop volume is new; it takes time to understand and achieve “optimum loop volume”.

Monitoring and multitasking

Another challenge is the constant need to monitor equipment. A CCR diver must observe the handset and HUD regularly to check setpoints and keep on top of the unit.

Initially, this workload feels intense. Divers fixate on the handset, neglecting awareness of teammates or the environment. Conversely, they might focus on external events and forget to check the handset. With practice, this balance improves, but repeated dives are required to develop a natural rhythm.

The danger of infrequent diving

How often a diver uses their CCR is one of the most critical factors to long-term safety. Skills require reinforcement, and too much time between dives increases risk. A diver who believes experience alone will protect them may be fooling themselves. Muscle memory decays, and procedures slip from memory.

Ironically, risk may be even greater for the “experienced but rusty” diver than for the novice. Complacency can creep in, convincing the diver that they remember everything, when in fact, details have slipped. This is why CCR is not a good fit for occasional divers. It demands consistent use to maintain competence, especially for those switching to CCR later in their diving careers.

Chasing courses versus building experience

Another trap is the temptation to pursue training for its own sake. Divers sometimes treat certification as a ticklist: air diluent, normoxic trimix, hypoxic trimix, cave CCR. But without diving experience between courses, progression can become unsafe.

The most effective path is to consolidate. Dive at the level you were trained for, build hours in varied conditions, and test your comfort gradually. Only once you are genuinely proficient should you move on to the next course. This approach makes advanced training less challenging and far more effective, especially for those switching to CCR with long-term technical ambitions.

Developing the CCR diving mindset

Ultimately, the CCR learning curve is as much about psychology as it is about skill. The unit requires a mindset of discipline, patience, and humility. Divers must accept that progress may feel slow and that setbacks are part of the process. They must also remain vigilant against complacency, because bad habits can creep in unnoticed. For divers switching to CCR, adopting this mindset early is essential to long-term safety and success.

Human Factors and Diving Behaviour

Why human factors matter in CCR diving

When switching to CCR diving, most divers focus on equipment, cost, and training. Yet accidents in rebreather diving often trace back not to hardware failure but to human error. This is where human factors come into play. Originally developed in aviation, the concept refers to how people interact with technology, procedures, and each other. Applied to diving, it highlights the psychological and behavioural risks that equipment alone cannot prevent.

Modern rebreathers are reliable. Compared with units of a decade ago, today’s designs show stronger build quality and undergo more thorough testing. But reliability still depends on the diver. A CCR remains safe only if divers maintain it correctly, assemble it carefully, and check it thoroughly before every dive. Skipping a step, rushing pre-dive checks, or letting discipline drift can undo the safety built into the unit.

The role of checklists

Checklists are central to CCR diving. They prevent divers from forgetting key steps when distracted or interrupted. Importantly, they only work if divers actively interact with them. Ticking off each item, physically or digitally, makes omissions far less likely. For those switching to CCR, adopting checklists from the start is one of the strongest safeguards against error.

Biases and decision-making

Human factors also involve understanding cognitive biases. Divers are prone to confirmation bias (“I checked, so it must be fine”), optimism bias (“It won’t happen to me”), and task fixation (focusing on one thing and missing another). In a CCR context, these biases can prove fatal.

For example, a diver may notice unusual handset readings but dismiss them because “the sensors were fine on the last dive.” Or they may convince themselves to continue despite equipment problems, normalising unsafe behaviour. Training introduces these concepts, but only discipline in real-world diving keeps them in check.

Drift and complacency

Perhaps the greatest long-term risk is complacency. After many uneventful dives, vigilance can fade. Divers may skip small steps- not analysing gas, not calibrating sensors, not completing a full pre-breathe. Each omission feels minor, but together they erode safety margins. Eventually, a failure occurs at the wrong time, with no buffer left.

I have seen this happen in practice many times. Divers begin well, ticking checklists and rehearsing drills. After 50 dives, shortcuts appear. By 100 dives, discipline may have eroded to the point where fundamental steps are skipped altogether. The rebreather does not forgive when human behaviour drifts in this way.

Suitability of the diver

Not every diver suits CCR. This is not a criticism but a recognition of psychology. A rebreather requires discipline, patience, and willingness to follow the same procedures- every time. Some people thrive under this structure. Others struggle, becoming easily bored or distracted.

When choosing whether to switch, ask yourself: Do you enjoy detailed preparation? Can you stay disciplined when repeating the same steps hundreds of times? Will you commit to following checklists, even when rushed or fatigued? These questions matter more than whether you can afford the unit or complete the course.

Human factors as the invisible risk

The risks of hypoxia, hyperoxia, or hypercapnia are easy to explain in training. They have physiological causes and clear consequences. Human factors are harder to teach because they remain invisible. Yet they may represent the biggest determinant of long-term CCR safety.

Switching to CCR diving is not only about mastering equipment. It is about recognising human fallibility and developing strategies to counter it. Checklists, discipline, honest self-assessment, moving away from a blame culture, and consistent practice are as critical as scrubber material or bailout cylinders.

The diver is the key component

Ultimately, the diver forms the most important part of the system. The unit cannot prevent complacency, resist drift, or correct bad habits. It cannot diagnose problems or help you to correct misinterpreted symptoms. It cannot stop you from assembling it incorrectly or diving it when unfit.

Gareth Lock has done significant work on human factors in diving. His research, case studies, and blogs are a valuable resource for anyone seeking to strengthen awareness of behavioural risks. His blogs are a wealth of information.

Understanding the Risks of CCR Diving

Why risk must be addressed openly

When switching to CCR diving, it is tempting to focus on the benefits: longer dives, helium savings, and closer encounters with marine life. Yet none of these matters if the diver does not fully understand the risks. Rebreathers are powerful tools, but they introduce unique hazards and amplify others already present in diving. Divers should not hide or downplay these risks. They can be managed- but only with discipline, preparation, and awareness.

Physiological risks in CCR diving

The major physiological risks associated with rebreathers are:

- Hypoxia (too little oxygen): If PPO₂ drops too low, the diver may lose consciousness without warning. This is the leading single cause of fatalities, often traced to divers entering the water with the oxygen cylinder closed. Consistent pre-dive checks prevent this entirely.

- Hyperoxia (too much oxygen): Excessive PPO₂ can cause central nervous system oxygen toxicity. Symptoms range from visual disturbances to convulsions underwater. Setting an aggressive setpoint for long exposures, repetitive dives, or consecutive days increases risk. Faulty or outdated oxygen sensors may also contribute.

- Hypercapnia (CO₂ retention): Scrubber failure, incorrect packing of sofnolime, high work of breathing, or poor technique can cause CO₂ retention. Symptoms include confusion, shortness of breath, and indecision- often leaving divers unable to act on what is happening. Prevention is better than cure, since few divers succeed in responding effectively underwater.

- Immersion Pulmonary Edema (IPE/IPO- Oedema in the UK): Fluid accumulation in the lungs during immersion. Rebreathers may increase the risk because of higher breathing resistance and dead space. Early symptoms can escalate rapidly; in severe cases, IPE can be fatal. It’s also a contraindication for diving; if you have IPE, you’ll likely never be able to dive again.

Professor Simon Mitchell has done a huge amount of work on diving physiology. He’s also a tech diver, so he often communicates with the tech diving community. Read his 5-part series on carbon dioxide here.

Cardiac health

The single most important area is cardiac health. Many CCR fatalities are linked to heart problems, not equipment malfunctions. However, this is more a middle-aged diver problem than a CCR-specific one.

Respiratory health is also more critical with CCRs. Rebreathers involve a higher work of breathing than OC, influenced by counterlung position and unit design. If a diver has reduced lung capacity or existing respiratory issues, they face a greater risk of CO₂ retention, which can lead to hypercapnia. For divers switching to CCR, this consideration is particularly relevant, as the unit magnifies respiratory workload compared with OC.

Decompression physiology and ageing

Decompression stress is another factor. On- and off-gassing efficiency reduces with age, and genetic and epigenetic differences affect how individuals respond to decompression. Older divers, therefore, face a greater risk of decompression sickness. For them, the ability of CCR to maintain a higher PPO₂ can be beneficial, since it reduces nitrogen uptake. Yet, divers must balance this benefit against the risk of oxygen toxicity, particularly on repetitive dives and consecutive diving days.

Additional risk factors include:

- Cold water and thermal stress.

- Exercise intensity during and after the dive.

- Dive profile (multi-level vs square profile).

- Individual susceptibility.

- Hydration status.

Dr Neal Pollock has given talks extensively on these factors, and his work remains a valuable reference for CCR divers. Watch his presentation at the BSAC diving conference- Thoughtful management of decompression stress (Diving physiology presentations- number 3 on the playlist).

Maintaining fitness for CCR diving

Because CCR demands consistency and discipline, divers must also maintain their physical readiness. Annual diving medicals are strongly recommended, not just for older divers but for anyone engaging in rebreather diving. Even apparently healthy divers may have undetected conditions that increase risk.

Regular aerobic exercise improves cardiac resilience, while strength and flexibility training reduce the risk of strain when handling heavy equipment. Even routine preparation- carrying units, assembling gear, and climbing ladders- is physically demanding. Divers who neglect fitness increase their risk not only underwater but also during topside handling of the equipment.

Equipment-related risks

While modern rebreathers are well-engineered, they remain safe only if maintained and assembled correctly. Risks arise when:

- Units receive poor servicing or are modified away from the manufacturer’s design.

- Divers skip pre-dive checklists or fail to confirm oxygen supply is on.

- O₂ sensors are not replaced regularly or are purchased in identical batches, leading to simultaneous failures.

- Counterlung position or modification raises the work of breathing beyond safe levels.

Divers can mitigate each of these risks, but only by following correct procedures every time.

Human factors and behavioural risks

Many CCR diving accidents relate less to physiology or equipment than to human behaviour. Drift, complacency, and normalisation of deviance are dangerous patterns. Examples include:

- Rushing or skipping checklists.

- Diving while unfit or overtired.

- Believing that “it won’t happen to me.”

- Misdiagnosing a problem underwater and making it worse.

In many cases, divers once learned the correct practices but gradually eroded them. This behavioural drift is one of the most serious risks in CCR diving.

The role of training in risk management

CCR training addresses all of these issues. Courses introduce hypoxia, hyperoxia, hypercapnia, and IPO in detail, alongside prevention methods. Drills for bailout, flushes, and manual setpoint control prepare divers for emergencies. Training also covers oxygen cell management, with best practice being to stagger replacements so cells are not all from the same batch, and to change them at least every 12 months.

However, training is only the beginning. Risk management depends on habits built over time. The diver must keep using checklists, stay current with research, and continue practising core skills.

Risks that cannot be eliminated

No system can make CCR diving risk-free. Even with perfect preparation, deep and long dives impose inherent physiological stresses. Oxygen toxicity, decompression stress, and IPE remain risks. The best a diver can do is reduce the likelihood through conservative choices, honest self-assessment, and disciplined practice.

Balanced perspective on CCR risks

It is important not to exaggerate. The risks of CCR diving are real, but they are not insurmountable. Divers who prepare, maintain discipline, and commit themselves can manage these risks. The key is honesty: understanding that technology does not remove risk, and that the diver’s behaviour is the single most important safety factor when switching to CCR.

Summary and Conclusion

The promise and the reality of CCR

Switching to CCR diving offers extraordinary possibilities. Longer dives, significant helium savings, optimised decompression, closer wildlife encounters, and the satisfaction of mastering advanced technology are all compelling reasons to make the move. For wreck divers, CCR opens opportunities to explore deeper and for longer without carrying excessive cylinders. For cave divers, it extends penetrations while providing flexibility in decompression management. For recreational divers, even at 30 metres, the comfort of the moist loop and the silence of bubble-free diving transform the experience.

The reality, however, is that CCR is not a shortcut. It does not simplify diving, and it does not remove risk. Instead, it may introduce new hazards for recreational and entry-level technical divers: hypoxia, hyperoxia, hypercapnia, immersion pulmonary oedema, and heightened decompression stress. It also amplifies the effects of human error, complacency, and drift. Technology supports the diver but does not replace the discipline, mindset, and awareness that safe rebreather diving demands.

The mindset required

CCR diving requires more than technical competence. It requires a mindset built on patience, humility, and honesty. The CCR learning curve can be long and frustrating, often feeling like one step forward and two steps back. Divers must accept this reality and commit to steady, consistent practice. They must also be honest about their own suitability: not every diver is naturally inclined towards repetitive checklists, careful maintenance, and conservative decision-making.

The diver is the most important part of the system. A rebreather cannot think, cannot prevent human error, and cannot save a diver from poor choices. Safety comes from the consistent application of habits: using checklists, replacing oxygen sensors on schedule, packing scrubbers correctly, maintaining the unit as designed, and remaining vigilant against complacency. For anyone switching to CCR, these habits determine whether the promise of the technology is realised safely.

The role of training and consolidation

CCR training provides the foundation, but it is only the beginning. Certification does not equal mastery. Real competence develops over dozens of dives in varied conditions, with skills reinforced until they become instinctive. Divers should resist the temptation to chase certifications — normoxic, hypoxic, cave — until they gain sufficient experience at each level. Those who consolidate after each course become far safer and more capable than those who treat training as a checklist.

Choosing the right instructor is equally critical. A supportive, experienced, and demanding instructor shapes habits that may last a diver’s entire CCR career. Where you train matters less than who trains you, and whether their standards and teaching style align with your goals.

The cost equation

CCR costs are often misunderstood. While helium savings are dramatic, especially for regular trimix divers, ownership also requires significant recurring expenses: sofnolime, oxygen, sensors, servicing, and spares. Training itself adds thousands of dollars, pounds, or euros. For divers making only a handful of deep dives a year, the economic case is weak. For those diving regularly, CCR may be both cost-effective and enabling, provided they also commit to the discipline it requires.

Balancing rewards and responsibilities

The rewards of switching to CCR are genuine: longer dives, financial savings on helium, better wildlife encounters, and increased comfort. But these rewards are balanced by responsibilities: higher complexity, increased risks, and the need for consistent discipline.

Being honest about the risks does not mean discouraging divers from CCR. These risks can be managed. With correct training, strong discipline, and the right mindset, CCR diving is safe, rewarding, and transformative. The key is to make the decision with eyes open, not blinded by the promise of technology alone.

Final thoughts

For me, CCR is not a replacement for open circuit, but an addition. I still dive single cylinders, twinsets, and sidemount. Each configuration has its place, and each offers unique value. CCR adds another tool, one that excels in certain environments but demands more of me in return.

If you are considering switching to CCR diving, reflect on your motivation, goals, and willingness to commit. Ask yourself whether you are prepared for the discipline, the costs, and the mindset required. If the answer is yes, CCR may open up the most rewarding and memorable dives of your life.

Further information

I’ve compiled a lot of rebreather videos on YouTube; some of them are about specific units. Go to the page here, and click on the Rebreather Information & discussion video. It’s a playlist. In the top right corner, click where it says “1/47” to see all the videos. Another playlist has a lot of videos about rebreather equipment, including tear-downs of different brands. You can view it on YouTube here.

For a broad overview of how rebreathers work, have a look at this page.

Shearwater has a good article about switching to CCR diving. View it here